by Marty Ropp, Allied Genetic Resources

Significant economic information, data, and research consistently suggest that maternal traits are two to three times more impactful to profitability than are growth and carcass traits. Despite this, many producers historically select almost solely for terminal traits when choosing their genetics, while continuing to claim that their focus is on the long term.

There is no doubt that advancing terminal and meat quality traits are crucial for the success of the beef industry as a whole, but this need not come totally at the expense of ranch profitability. Even poorly thought-out decisions, like not utilizing planned crossbreeding and hybrid vigor in the cow herd, are terminal choices that erode profitability far out into the future.

When to Select for Terminal Traits

Certainly, there are circumstances where producers should select largely or even solely for terminal traits. Producers who do not retain any replacement females from their herds should absolutely prioritize terminal value. Also, those who plan to exit the business in the next three years can focus solely on terminal traits. Beefon-dairy and niche breed scenario enterprises also fall onto this list where terminal traits are king. For those exiting the industry without new generation succession on the ranch, he or she might be best off to just harvest those calf crops off the land with as much weight and gross income as possible.

Why Maternal Trait Selection Matters

For the majority, however, who keep their own replacement females and value enterprise success for the long term, maternal, value-generating genetics are crucial in the majority of genetic decisions. For the increasing number of producers purchasing their replacements, it is critical to ensure whomever you purchase from is prioritizing maternal traits, and not simply marketing weight and terminal value.

Fortunately for the beef industry, marbling is the overwhelming influencer of carcass value today, and it is not strongly correlated to fertility or longevity traits either positively or negatively. The only scenario where there may be a relationship between marbling and maternal traits is when a genetic line may have been selected highly for a specific trait like marbling with little or no selection for fertility and longevity traits. In that specific case, if a line is limited to a small number of highly influential sires, the artificially high genetic influence of these selected sires could create issues in the maternal trait complex. This is not because the traits are highly correlated, but instead because their negative maternal genetic effects were so highly concentrated due to single trait selection bias on that population with no available tools for co-evaluation of high-value maternal profit genetics.

The focus of genetic selection is leaning toward terminal traits, without a solid plan to maintain profit in the long run. While there is appeal to this plan, it doesn’t consider future implications.

As stated, it is clear that today the focus of genetic selection is leaning toward terminal traits, without a solid plan to maintain profit in the long run. Purchasing big, stout bulls with the most growth genetics, at a high price, is becoming the norm. While there is appeal to this plan, it doesn’t consider future implications. Most of these sires are genetically terminal. Traits like actual weaning weight are easy to promote and have been pushed, and it’s simply easier to sell the short-term hope of bigger calves 18 months from now.

The benefit of maternal traits, which aren’t fully realized for many years and several generations in the cow herd (five to 15 years), can be much more difficult to market. Saying, “Buy these bulls and in eight to ten years you will be very happy and more profitable,” is a tough, but important sell. Most producers envy those trouble-free and profitable cow herds, generated by many years of commitment to cow profit traits. In fact, we often try to buy females from herds where maternal traits have been prioritized long term. Still, the promise of heavy calves in the near term distracts producers from longer-term goals.

These shortsighted decisions will likely cause operations to suffer through cows that are too expensive to maintain and leave the herd much too quickly in the future. When these females become too expensive to maintain, producers might blame anything from the breed of bulls used, to management systems like health or mineral programs. The bottom line is that your genetic decisions will absolutely affect your enterprise profitability for years and years to come, which is why selection for genetics that promote cow longevity, reduced cost, and ultimately profit is so important. It’s imperative that the industry doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, which ultimately forced producers to make drastic genetic changes.

Common Challenges

There is historical marketing and selection bias shared by many promoters for pounds and “power.” The old adage “we sell cattle by the pound” is true, but can be misleading, as it may have little or nothing to do with actual, long-term enterprise profitability. While it is true that many commercial producers sell calves by the pound each year, there are much better measures of total gross sales than just individual calf weight. Total weight produced by the same cows can also be greatly affected by maternal traits that are not related to and can even be antagonistic to growth.

More calves weaned per cow exposed, less dystocia, faster return to estrus, more calves born in the first 21 days of the breeding season, and a higher percentage of calves born to mature cows than heifers because of greater cow longevity — these are all non-growth-related factors that deliver added income with little or no added cost of production. The bottom line is that when it comes to selecting for growth traits, none of the extra pounds of calf generated come for free.

Individual cow costs are not equal. Therefore, evaluating a cow based on how large the calf she weaned doesn’t paint the full picture, especially if she produced a calf that put enough stress on her system that she bred back late or came in dry. Cows that produce these high-weaning-weight calves are often larger, require more feed and resources, and as a result may often stay in the herd for a shorter period of time. As a rough example, a 1,600pound cow will consume approximately one ton more delivered winter feed than one that weighs 1,200 pounds (based on 150-day feeding period). Certainly, summer and long season stocking rates are reduced as well based on forage consumption, and that difference results in the potential to graze fewer cows on the same land base. A heavier cull cow does return more salvage value, but after ten years of added maintenance it certainly isn’t enough more. Also, heavier calves bring less per pound, so the value of each additional 100 pounds of weaned calf is much less than the last 100 pounds. If those resources were used to make more calves instead of just heavier ones, the value of each pound of calf produced for the operation would be significantly higher.

500 pounds @ $3.50/pound = $1,750 (Every pound produced is worth $3.40)

600 pounds @ $3.20/pound = $1,920 (+$170 or per $1.70/additional pound)

700 pounds @ $2.90/pound = $2,030 (+$110 or per $1.10/additional pound)

We well know that the number of live calves a female produces and the earlier she calves in the calving season have profound effects on lifetime production and therefore reduce the costs associated with developing her replacement. Most of us attribute added longevity to fertility, but other genetically influenced traits like milk yield, efficiency, mature cow maintenance requirement, environmental adaptation, physical structure, and even disposition can and do affect cow longevity and profit. Crossbred commercial cows, on average, last at least one year longer in production than their purebred counterparts.

Moving Forward

Having emphasized the importance of maternal, long-term trait selection, it’s important to note that terminal traits are still significant. Improving genetics for efficient growth, carcass yield, and marbling are crucial for the success of the larger beef industry. Down-chain, other segments face cost increases too, but they only live with the genetics that are delivered to them for a relatively short period of time, compared to a cow-calf operation (six months vs. ten-plus years). With that in mind, segmenting production seems like a pragmatic solution to general improvement for all segments. Perhaps some of these arguments and skyrocketing costs of production might finally drive the commercial beef business into a future with maternal herds and terminal herds, even on the same ranch. The idea being to generate maternal genetics to help produce the lowest-cost and longest-lived females possible, then cordon off a large segment of the nation’s cow herd to be mated to terminal options to create the most profit those cows can generate. It works in other industries, but these structures have just been a harder sell for many in the beef business, partly because of the relatively low reproductive rate in cattle and the unique management challenges of the beef industry. Despite those traditional hurdles, we will likely see more maternal vs. terminal production herds as we move into a more efficient and precisely managed future.

Down-chain, other segments face cost increases too, but they only live with the genetics that are delivered to them for a relatively short period of time, compared to a cow-calf operation.

We are learning more every day about which genetics make the most profitable commercial females for the beef industry, and the results will be sobering to many who have always been fixated on a specific phenotype. Sure, there are crucial phenotypes related to cow longevity. Udder longevity, feet longevity, appropriate (but not extreme) body condition, and other factors have merit to evaluate. Those traits matter for maximum longevity and profit.

The myths about the big, stout, square-hipped, over-fleshed, stout-boned, feminine-headed, massive-bodied cow being the longest-lived and most profitable commercial cow, however, just aren’t panning out. Expect some surprises when the dollars are really counted. Cows that produce the most profit over their lifetime in the commercial sector are apt to be below average for size, average muscled at best, more refined appearing, definitely crossbred, and maybe even a little “plain,” at least based on today’s definition. We are discovering it is far better to find the more profitable cows and select for their genetics and physical attributes than it is to decide the physical attributes we prefer up front and hope they are the same as the ones that generate the most profit to the ranch and the larger beef business.

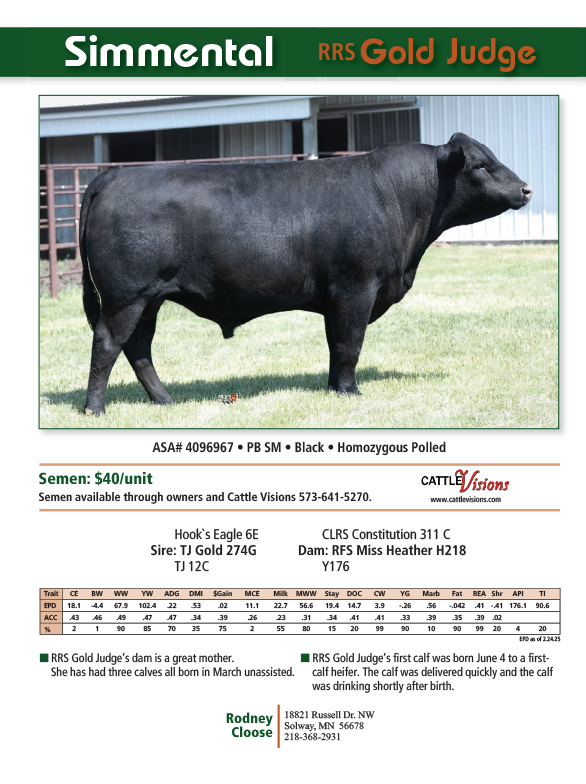

Thankfully, there are now solid genetic and genomic evaluation tools. The STAY EPD, maternal indexes, profit indexes ($API and $TI), and precision genomic sorting (please reference specific tools available through Allied Genetic Resources) can help us move cow longevity in a positive direction, faster, and more consistently. The old adage that “maternal traits are lowly heritable, so we can’t make much progress,” has led to plenty of misunderstanding. Genetics actually play an enormous role in maternal profitability, it was just our challenges with measuring those traits accurately and consistently that made the “E” (Environment) such a large part of the equation and the “G” (Genetic) component seem so small, resulting in low heritability estimates. Now that we can better evaluate fertility, longevity, and the other factors involved in the maternal trait complex, the realized heritability is improving each and every year.

These tools should be used when making bull buying decisions more often, rather than fixating on marginally useful, often-unrepeatable, and highly variable data like actual weaning weights. If more maternal trait tool use and emphasis is employed, our cow-calf operations will definitely have a longer and more profitable future, guaranteed. .